Andry Hernández Romero lights up when he talks about Italian food. “I love pasta,” he said, sitting at his parents’ house in Capacho Nuevo, in the Venezuelan state of Táchira, on the border with Colombia. He’s wearing a t-shirt with an image of himself holding a bejeweled crown. It’s been almost four weeks since he got his life back. He sports a smile that momentarily erases the weight of the past year from his face. The 32-year-old gay Venezuelan makeup artist has survived things that would break most people. But in conversation, he peppers his story with warmth, dignity, and an insistence on seeing the beauty in small pleasures.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate’s email newsletter.

He’s soft spoken, gracious, and disarmingly kind, yet confident and wise. “It’s so nice to see you, thank you for wanting to have this conversation,” he said. That mix of lightness and strength is striking when you know where he’s been: 125 days in El Salvador’s notorious Terrorism Confinement Center, or CECOT, a dystopian mega-prison and the most secure and most brutal detention center in the Americas. President Donald Trump had declared war on immigrants from Venezuela and made a deal with El Salvador’s strongman president, Nayib Bukele, to house hundreds of men the U.S. government did not want in the country. In Hernández Romero’s case, that meant removing a gay asylum seeker to a country he had never lived in and leaving him at the mercy of a system designed to crush those it labeled enemies.

Related: Inside the movement that freed gay makeup artist Andry Hernández Romero from a hellhole

“I want the world to know that being Venezuelan is not a crime,” Hernández Romero told The Advocate in an exclusive interview, which was conducted through an interpreter.

From California to Texas to CECOT

Before El Salvador, Hernández Romero had already endured months in U.S. immigration detention, first in California, then in Texas, after crossing the border legally at the San Ysidro port of entry in August 2024 to attend an asylum appointment using the Biden administration’s CBP One app. He had fled persecution based on his political beliefs and sexual orientation. He was detained immediately, and within a week, officials accused him of belonging to the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua gang based solely on two tattoos: the words “mom” and “dad” with a crown.

Related: Andry Hernández Romero explains how he survived CECOT after the U.S. government disappeared him

On March 15, he was deported under the Trump administration’s revived use of the Alien Enemies Act, a centuries-old wartime law historically used to detain or deport immigrants en masse. He had no ties to El Salvador and was sent there without a hearing. Hernández Romero recently told The Bulwark’s Tim Miller that ICE officers lied to detainees about their destination, staging delays in Honduras before landing in San Salvador late on a Saturday, when U.S. courts were closed, “the perfect day to take us out of the country,” he said. Once off the plane, “They started hitting and kicking us … between two officers, they dragged us down the stairs.”

A first group of 2,000 detainees are moved to the mega-prison Terrorist Confinement Centre (CECOT) on February 24, 2023 in Tecoluca, El Salvador.Presidencia El Salvador via Getty Images

Related: Gay asylum-seeker’s lawyer worries for the makeup artist’s safety in Salvadoran ‘hellhole’ prison

He was processed into CECOT, where he would spend the next four months under conditions that human rights groups have called torturous. The last time anyone from the U.S. saw him was when a Time photojournalist captured his arrival, when guards shaved his head and he fearfully declared, “I’m gay,” while calling out for his mom. He had been disappeared.

A day in hell

Hernández Romero hesitates to speak of the sexual and physical abuse he reported when he first arrived back in Venezuela. A guard, he told reporters, made him perform oral sex while others ran their clubs over his body.

Related: Gay makeup artist Andry Hernández Romero describes horrific sexual & physical abuse at CECOT in El Salvador

However, his account of “normal” life inside the prison is almost clinical in its detail.

There were no mattresses, blankets, or pillows. Beds were made of stacked metal slabs. Fluorescent light bathed all corners of the cells that held dozens of men.

Detainees woke up between 4:30 and 6:00 a.m. The first order of the day was roll call, then a brief window to bathe before breakfast. Mornings were often filled with Bible reading or whispered small group discussions, he said.

There’s no television or time outdoors.

After a midday meal, afternoons were devoted to exercise or waiting for the prison pastor to arrive with scripture. Dinner was served around 4:30 p.m., and lights out at 9:00 p.m.

Related: Gay Venezuelan asylum-seeker ‘disappeared’ to Salvadoran mega-prison under Trump order, Maddow reveals

It was a routine that masked the reality: men living under constant surveillance, with guards reminding them that they might never leave. “They told us we would die there, that we would spend more than 20 years condemned as terrorists,” he told The Advocate.

Faith became his anchor. “Our faith was what allowed us to carry such a heavy burden, the cross each of us carried on our backs,” he said. “When the pastor read to us, we felt lighter.”

The only out gay man at CECOT

Hernández Romero, who is Catholic, said he was the only out gay man in his unit. In a hyper-masculine environment, that might have spelled danger. But he said mutual respect kept tensions at bay.

“I respect them, and they respected me,” he said. “Before being gay, I am a man. I can adapt to their conversations about soccer, mechanics, and motorcycles, just as they listened when I spoke about other things. No one crossed any lines.”

That respect, however, did not mean acceptance. It was survival: knowing when to blend in, when to listen, and when to keep to himself. “I belong to the LGBTQ+ community, to the diversity,” he said. “From day one, I asked for respect, and I gave respect.”

He joined his cellmates in exercise, debates, and discussions about politics, religion, and everyday gossip — anything to make the days pass more quickly.

The coalition on the outside

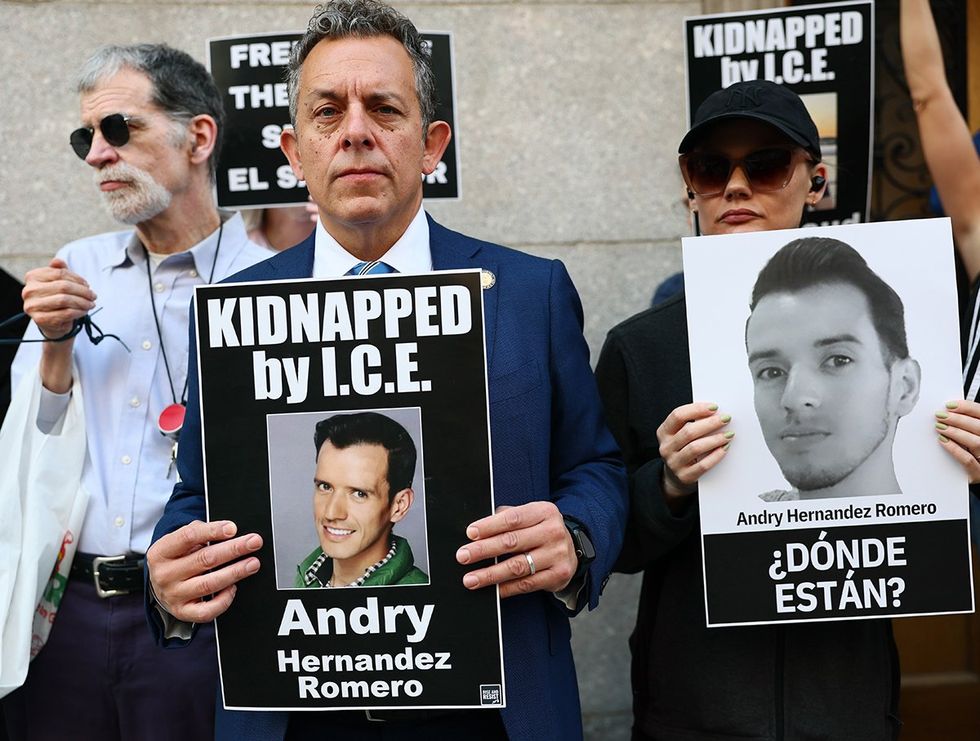

In the U.S., Hernández Romero’s case had become a cause for activists, lawmakers, and everyday Americans who saw in him a symbol of both injustice and resilience. His face appeared on banners at Pride events, on posters held aloft outside the U.S. Supreme Court. His story was told on national television and podcasts by journalists and advocates.

Related: Hundreds rallying at Supreme Court demand Trump return disappeared gay asylum-seeker Andry Hernández Romero

“I never imagined my name, my image, my story would be so influential in the United States,” he said. “I never thought a large part of the American community would identify with the problem we were facing. It feels very beautiful to be that spokesperson for many, to let them know they are not alone, that the community is always there.”

He added, “If something happens to one of us, it happens to all of us.”

For Hernández Romero, the support was more than symbolic. It was a lifeline. “When someone takes a moment from their life to go to a march, to post an image, to send a message of love and solidarity, the least I can do is show them gratitude and treat them well in return,” he said.

The night before freedom

His release came as suddenly as his imprisonment. For months, false promises had been part of the psychological grind. So when guards told him, “Today you’re leaving,” he didn’t believe them.

It wasn’t until the pastor, his voice shaking, told the group, “The miracle is done. Tomorrow will be a new day for you,” that Hernández Romero allowed himself to hope. In the early hours of July 18, guards ordered the 252 Venezuelan men deported from the U.S. to strip to their boxers and gave them minutes to shower. They were issued civilian clothes, loaded onto buses, and driven to a military base. The men rode in silence, terrified and anxious. Still, no one knew where they were headed, Hernández Romero said.

Then a man boarded the bus and greeted them: “Buenos días, chamos,” Venezuelan slang for “friends” or “buddies.” Hearing the Venezuelan vernacular made it clear: freedom was on the horizon. Soon, they saw the Venezuelan military planes waiting on the tarmac. An officer told them, “You may be in Salvadoran territory, but you are now on Venezuelan soil. No one can touch you.”

Now that he’s home, Hernández Romero’s lawyers are working with him to consider his legal options. In the aftermath of a contentious election in 2024, the Venezuelan government began cracking down on speech and disfavored groups, including LGBTQ+ people. Advocates warn that under the current regime, he remains a potential target.

Two sentences served

For Hernández Romero, release didn’t erase the damage done to him or his family. “We served two sentences,” he said. “The one we endured in that hell, and the one our parents lived with an imprisoned pain that only ended when they saw us return.”

In May, while he was in captivity, gay U.S. Rep. Robert Garcia, a California Democrat and the ranking member on the House Oversight Committee, pleaded with Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem to provide a sign of life to Hernández Romero’s mother. She refused.

Related: Andry Hernández Romero’s family desperate for word on gay asylum-seeker who Trump vanished over 100 days ago

His parents suffered greatly, not knowing if they’d ever see him again. He said that since his return, they have begun sleeping, eating, and smiling again, their mental health slowly recovering after months of anguish.

The road ahead

Since returning to Venezuela, Hernández Romero has been tending to his physical and mental health. He is working with his legal team, including Southern California-based Immigrant Defenders Law Center cofounder and executive director Lindsay Toczylowski, to clear his name and to find a safe and permanent home. The Trump administration had claimed that he and others were “the worst of the worst” and deserved to be imprisoned indefinitely.

Toczylowski told The Advocate in July that the political reality of the U.S. makes it unlikely he will be safe there. But, he may eventually find a home in Europe. “We have churches in Spain and the Netherlands and Canada reaching out to us, offering to support him, offering to take him in if we can get him out,” she said in April.

For Hernández Romero, most immediately, he wants his good name back. “I want the world to know I am not a criminal. I am a stylist, a makeup artist. My only weapons are two brushes,” he said.

Even after losing all his professional supplies during his detention, Hernández Romero’s passion for makeup artistry remains undimmed. He still lights up when talking about his favorite products. Rebuilding his kit is part of his plan to rebuild his life, a step toward becoming, as he put it, “the Andry full of colors, full of glitter, the Andry who helps those in need.”

Gratitude above all

Since returning home, Hernández Romero has been reclaiming the everyday joys he once took for granted. “Every morning, I thank God,” he said. “That’s how I start a good day.” He loves to read, hike into the mountains to connect with nature, travel, spend quality time with friends, and go to the movies. “Mostly, I like to eat, because I have no bottom. I eat a lot,” he said, laughing. He’s also easing back into makeup work; after his Friday afternoon interview with The Advocate, he had an appointment to do hair and makeup for a client.

Not long after he came home, Hernández Romero joined a procession honoring the Virgin Mary. He and a friend wore shirts with his image and the words “Libertad para Andry” or “Freedom for Andry.” He said people in the crowd began to approach him. “You’re the one from CECOT,” they told him. “You’re the makeup artist. You’re the one from TikTok.”

For Hernández Romero, the recognition wasn’t about celebrity; it was about connection. Each person who stopped him was a reminder that the fight to free him had resonated far beyond U.S. borders, and that he wasn’t walking alone.

The months inside, Hernández Romero said, left a lasting imprint. “I learned a lot of patience, something I didn’t have before,” he said. He became more positive, starting each day in detention by telling himself, “Hoy me voy” — today I’m leaving — and more tolerant of differences, learning to respect opinions even when they clashed with his own. He also stopped rushing to judgment.

At the same time, the experience revealed a flaw he’s still working on: his perfectionism. As a designer, he used to exhaust himself trying to control every detail, from buying fabrics to sewing garments, but now, he said, he’s learning to trust the people in his circle who want the best for him.

He has always been open about his sexuality, he said, but knows many cannot express themselves because of the stigma and the cliché of “what will people say.” Now, he hopes to use his new platform to fight that silence, channeling it into a foundation and other projects so they can “grow and be successful.”

Hernández Romero doesn’t dwell on revenge or bitterness. Instead, he’s focused on gratitude for the coalition that fought for him, for his family’s strength, for the strangers who saw his face and decided his life mattered.

“It’s gratifying to see people take a minute from their day to send me a religious phrase, a message of love, of support,” he said. And to the LGBTQ+ community in the U.S., he has a message. “Here you have a Venezuelan brother who loves you, too. This fight will go on for a long time, but I know we will meet someday,” he said.